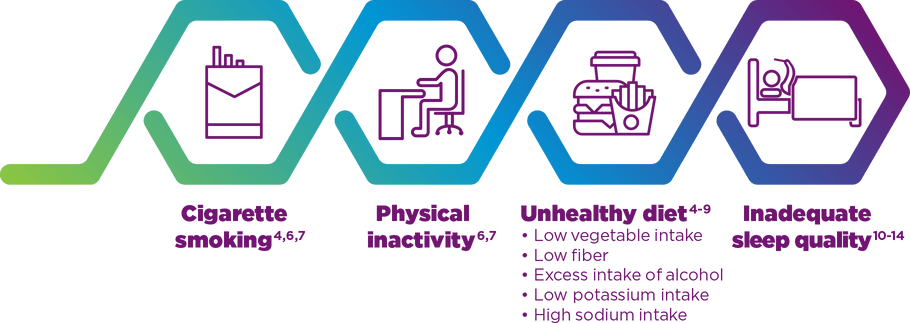

Modifiable Risk Factors Can Impact Risk of CV Disease

Most Common Modifiable Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease4-14

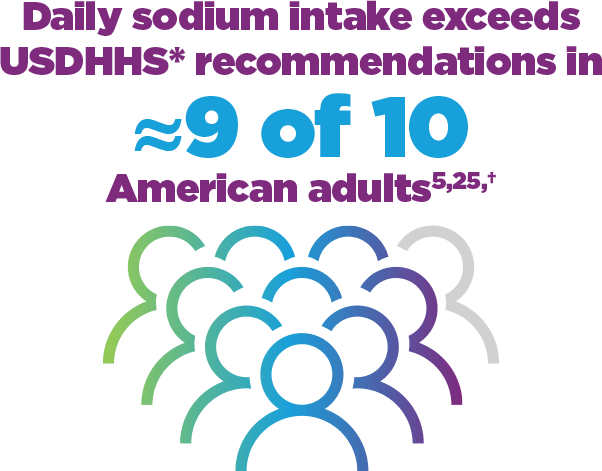

Excessive sodium intake is a modifiable risk factor for CV disease5

There is consensus among health organizations, including the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA),4,15 that excess sodium intake is associated with increased BP,16,17 a strong risk factor for CV disease in the general population.18-20 Increased sodium intake is also believed to have a direct effect on negative CV outcomes, including coronary heart disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, and stroke.21-24

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES; 2009-2012), in about 9 of 10 American adults (aged ≥19 years), sodium intake exceeded the recommended upper intake limit of 2300 mg/day.5,25

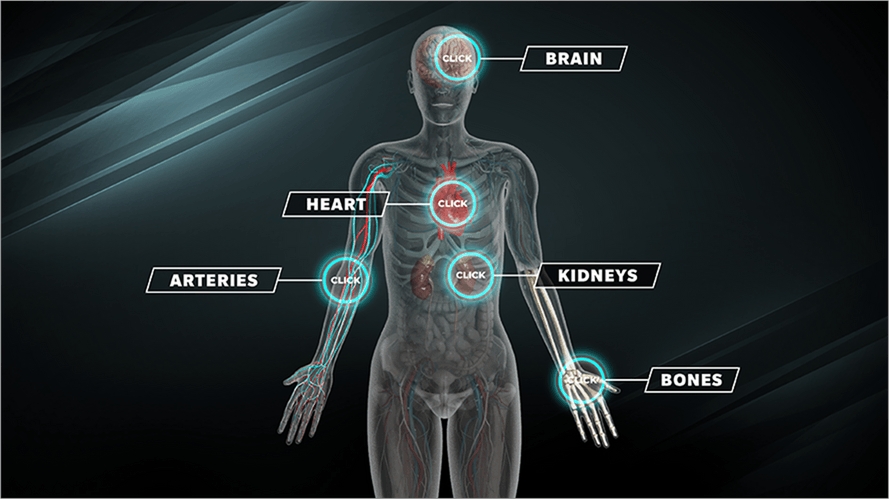

Chronic elevated dietary sodium can affect the heart, brain, kidneys, and other body systems26,27

LEARN MORE:

Interactive Infographic

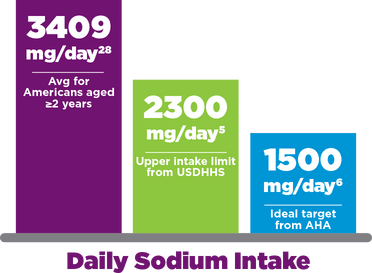

According to an analysis of data from the 2013-2014 dietary intake portion of the NHANES, the mean dietary sodium intake for Americans ≥2 years was 3409 mg/day—which far exceeds the 1500-mg/day ideal target endorsed by the AHA.6,28

To learn more about the AHA recommendation, go to heart.org.

*The US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) recommends a sodium upper intake limit of 2300 mg/day.25

†Based on 2009-2012 NHANES data from 14,728 participants aged ≥2 years.5

In addition to daily intake from foods and drinks, sodium in both over-the-counter and prescription medications, including certain narcolepsy medications, can contribute to patients’ total sodium intake.28,29

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), recognizing that most Americans, irrespective of comorbidities, consume excessive sodium, has recently set targets to decrease sodium intake from commercially packaged, processed, and prepared foods to reduce the risk of developing CV disease.30,*

*The FDA’s voluntary guidance for industry related to commercially packaged, processed, and prepared foods includes the short-term goal of helping Americans to reduce their average sodium intake by 12% (from 3400 mg to 3000 mg of sodium per day) over the next 2.5 years and plans for further iterative reductions in the future.30

Significant reductions in sodium may reduce the risk of developing CV conditions in the general population31

In 2019, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine reported 2300 mg/day as the chronic disease risk reduction intake level for sodium in people aged 14 years and older—ie, the level above which intake reduction is expected to reduce chronic disease risk within an apparently healthy population.32 Furthermore, a consensus of 11 professional organizations* recommends a goal of at least a 1000-mg/day reduction of dietary sodium intake in most adults as one of the best proven nonpharmacological interventions for prevention and treatment of hypertension.4 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines reiterate this recommendation.33,†

*2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.4

†2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.33

Sodium excretion and CV risk

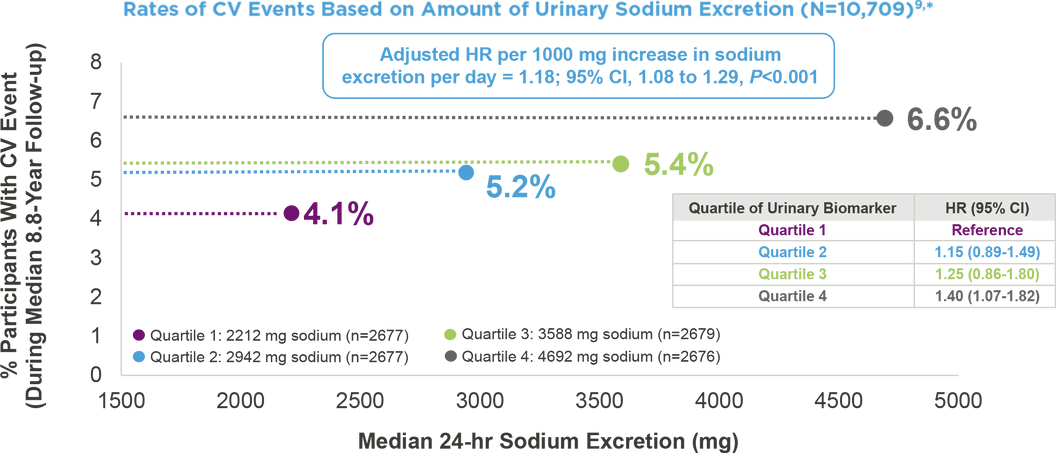

A meta-analysis of 10,709 participants from 6 studies showed that higher 24-hour urinary sodium excretion was associated with higher CV risk in analyses that controlled for confounding factors9

Each

1000-mg increase

in 24-hour

urinary sodium excretion is associated with an 18% increase in CV risk9,*

*A meta-analysis of individual-participant data from 6 prospective cohorts of generally healthy adults. Sodium excretion was assessed with the use of at least two 24-hour urine samples per participant. The primary outcome measure was a cardiovascular event, including coronary revascularization or fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke. Hazard ratios were estimated from models adjusted for potential confounding factors, including age, sex, race, educational level, height, body-mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, history of diabetes and elevated cholesterol status, family history of CV disease, 24-hour urinary potassium excretion, and total energy intake and modified Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet quality score.9

Significant reductions in sodium may reduce the risk of developing CV conditions in the general population31

A coronary heart disease policy model† projected that a US population–wide reduction in dietary sodium intake of 1200 mg/day can reduce the annual number of new cases of coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, and any-cause deaths.31

†The Coronary Heart Disease Policy Model, a computer simulation of heart disease in US adults aged 35-84 years.31

READ NEXT:

Learn more about chronic elevated

dietary sodium

- Black J, Reaven NL, Funk SE, et al. Medical comorbidity in narcolepsy: findings from the Burden of Narcolepsy Disease (BOND) study. Sleep Med. 2017;33:13-18.

- Cohen A, Mandrekar J, St Louis EK, Silber MH, Kotagal S. Comorbidities in a community sample of narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2018;43:14-18.

- Ohayon MM. Narcolepsy is complicated by high medical and psychiatric comorbidities: a comparison with the general population. Sleep Med. 2013;14(6):488-492.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Hypertension. 2018;71(6):e136-e139] [published correction appears in Hypertension. 2018;72(3):e33]. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324.

- Jackson SL, King SM, Zhao L, Cogswell ME. Prevalence of excess sodium intake in the United States—NHANES, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(52):1393-1397.

- Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e528.

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613.

- Salehi-Abargouei A, Maghsoudi Z, Shirani F, Azadbakht L. Effects of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-style diet on fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular diseases—incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis on observational prospective studies. Nutrition. 2013;29(4):611–618.

- Ma Y, He FJ, Sun Q, et al. 24-Hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion and cardiovascular risk N Engl J Med. 2022;386(3):252-263.

- Quan SF. Sleep disturbances and their relationship to cardiovascular disease. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2009;3(1 suppl):55s-59s.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep and Chronic Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/chronic_disease.html. Page last reviewed: August 8, 2018.

- McAlpine CS, Kiss MG, Rattik S, et al. Sleep modulates haematopoiesis and protects against atherosclerosis. Nature. 2019;566(7744):383-387.

- Dauvilliers Y, Jaussent I, Krams B, et al. Non-dipping blood pressure profile in narcolepsy with cataplexy. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38977.

- Grimaldi D, Calandra-Buonaura G, Provini F, et al. Abnormal sleep-cardiovascular system interaction in narcolepsy with cataplexy: effects of hypocretin deficiency in humans. Sleep. 2012;35(4):519-528.

- WHO Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children. World Health Organization; 2012.

- Elliott P, Stamler J, Nichols R, et al. Intersalt revisited: further analyses of 24 hour sodium excretion and blood pressure within and across populations. BMJ. 1996;312(7041):1249-1253.

- Mente A, O’Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, et al; PURE Investigators. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):601-611.

- Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A; International Society of Hypertension. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371(9623);1513-1518.

- Kannel WB. Blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor: prevention and treatment. JAMA. 1996;275(20):1571-1576.

- Kokubo Y, Matsumoto C. Hypertension is a risk factor for several types of heart disease: review of prospective studies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;956:419-426.

- Institute of Medicine. Sodium Intake in Populations: Assessment of Evidence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013.

- Gardener H, Rundek T, Wright CB, Elkind MS, Sacco RL. Dietary sodium and risk of stroke in the Northern Manhattan study. Stroke. 2012;43(5):1200-1205.

- Rodriguez CJ, Bibbins-Domingo K, Jin Z, Daviglus ML, Goff DC Jr, Jacobs DR Jr. Association of sodium and potassium intake with left ventricular mass: coronary artery risk development in young adults. Hypertension. 2011;58(3):410-416.

- Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4567.

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.

- Farquhar WB, Edwards DG, Jurkovitz CT, Weintraub WS. Dietary sodium and health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(10):1042-1050.

- Robinson AT, Edwards DG, Farquhar WB. The influence of dietary salt beyond blood pressure. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2019;21(6):42.

- Quader ZS, Zhao L, Gillespie C, et al. Sodium intake among persons aged ≥2 years—United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(12):324-328.

- Perrin G, Korb-Savoldelli V, Karras A, Danchin N, Durieux P, Sabatier B. Cardiovascular risk associated with high sodium-containing drugs: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180634.

- Voluntary Sodium Reduction Goals: Target Mean and Upper Bound Concentrations for Sodium in Commercially Processed, Packaged, and Prepared Foods: Guidance for Industry. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition; 2021.

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):590-599.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019.

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2019;140(11):e647-e648] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2020;141(4):e59] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2020;141(16):e773]. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e563-e595.

Research has demonstrated an increased prevalence of certain comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular (CV) and cardiometabolic conditions, in patients with narcolepsy compared with matched controls.1-3 Certain risk factors for developing CV conditions can be modified by maintaining a healthy lifestyle.4-13